Exclusive Explanation of Molecular Cooking (Part 1)

Editor's Note: Guo Hongxiao, the pioneer of molecular cooking and the godfather of molecular gastronomy, has made remarkable contributions to the internationalization of the catering industry. Today, our Guangdong and Hong Kong Catering Micro Magazine has invited Master Guo Hongxiao to share his knowledge of molecular cooking and present over 30 of his latest molecular gastronomy dishes.

Section 1: Introduction to Molecular Gastronomy

(Guo Hongxiao's work: -200-degree strawberry)

1. Introduction to Molecular Gastronomy

The term molecular gastronomy was coined in 1988 by Hungarian physicist Nicholas Kurti and French chemist Hervé This.

Molecular gastronomy is a cutting-edge culinary discipline. It uses a scientific approach to understand the physical and chemical processes and principles of food molecules, then applies the resulting knowledge and>

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Icy Liquid Nitrogen Ice Cream)

Molecular gastronomy, directly translated as molecular gastronomy, is a field where scientists use chemistry, biology, and physics to explain why food tastes delicious. Simply put, it explains why it should be cooked this way. Herve This once proposed five goals for molecular gastronomy:

① Study the principles behind various cooking techniques. ② Understand the chemical reactions between ingredients in recipes after processing. ③ Develop new products, tools, and cooking methods. ④ Create new dishes. ⑤ Promote the contribution of science to daily life.

Herve This, the father of molecular gastronomy, believes that molecular gastronomy is:

1. Research social phenomena related to catering activities;

2. Study the chemical and physical properties of various artistic ingredients in catering;

3. Study the technological components of F&B; define patterns, accurately collect and test them, and identify causes.

Herve This also pointed out the difference between molecular gastronomy and molecular cuisine.

Molecular gastronomy is a scientific research, and the cuisine derived and applied from this research is called molecular cuisine. So we can say that molecular gastronomy is about "knowing why" and molecular cuisine is about "knowing how".

But what is surprising is that among the 50 best restaurants in the world in 2006 named by the British "Restaurant" magazine, the top three are all restaurants of this type. Whether it is ElBulli, The Fat Duck, or Pierre Gagnaire, they are all well-known leaders of this culinary genre and are also Michelin three-star restaurants with a high reputation in the world. Therefore, we have to pay attention to this genre that is having an increasingly profound impact on the world but is still unfamiliar in China.

Just as Einstein, who was not a physicist, created new theories in physics, the first initiator of molecular gastronomy was not a professional chef, but a physicist Nicholas Kurti and a chemist Herve This.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Glass Vegetable Salad)

As early as 1969, Nicholas Kurti, then a renowned foodie while teaching at Oxford, once lamented, "It's a tragedy that we can measure the temperature of Venus' atmosphere, but we don't know why the food in front of us tastes so good." So he began studying food from a scientific perspective, proposing that pineapple juice, which contains enzymes, can make meat more tender, and proposed cooking principles such as slow cooking.

In 1992, 84-year-old Nicholas Kurti and Herve This founded the International Workshop on Molecular Gastronomy in Erice, Sicily, marking the first time that professional chefs and university professors collaborated to study the principles behind food.

Although molecular gastronomy is new, it quickly gained popularity thanks to two things: the publication of "On Food and Cooking" by chemist Harold McGee, and the rise to fame of Spanish chef Ferran Adrià. Adelman, who owns a restaurant called El Bulli in the small town of Rosas in Catalonia, Spain, experimented, and still does, with different types of jellies and other proteins. He tried using calcium chloride to shape juices—or any liquid imaginable—into tiny, delicate balls like fish roe. He experimented with wildly varying structures and temperatures, and other chefs followed suit.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Crispy Cherry Foie Gras)

2. Definition

Molecular gastronomy, simply put, is the scientific understanding of the physical and chemical properties of food molecules to create "precise" cuisine. Using additives, ingredients are modified to alter their texture and appearance. This culinary concept transcends our current understanding and imagination, transforming food from simply food into a sensory experience of sight, taste, and even touch. It is a scientific approach to cooking founded on science. Using a scientific perspective, we gain a deeper understanding of cooking, from the macro to the micro. Using scientific methods, we achieve more scientific, healthy, fashionable, and nutritious cooking. It is a distinct artistic style within European and American cuisine.

In simple terms, it is the process of using today's most advanced science and technology, combined with the most precise measurement methods, through some chemical and physical methods to create the most wonderful food.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Low-temperature slow-cooked hot spring eggs)

2. Molecular Gastronomy Culinary Events

Molecular Cuisine Timeline

Agar was already being used in 1700 BC.

In 1682, French mathematician and physicist Denis Papin discovered the method of extracting gelatine.

1794年 Sir Benjamin Thompson发表他的论文: On the construction of kitchen fireplaces and ktchen utensils, together with remarks and observaions relating to the various processes of cookery, and proposal for improving that most useful art

1844 Nobel Prize winner in Chemistry Justus von Liebig publishes: The Processing, Chemical Reactions and Effects of Food

In 1912, French chemist and physicist Louis Camille Maillard discovered that protein-containing foods absorb aroma during frying and roasting, which became known as the Maillard reaction.

1969 Nicholas Kurti's Royal Lecture: A Physicist in the Kitchen

In 1974, food chemist Bruno Goussault and chef Georges Pralus, Pieere Troisgrois first used the new cooking technique of Sous-Vide, namely vacuum low-temperature cooking.

1984 American scientist Harold McGee published his first book on science in the kitchen

In 1988, Nicholas Kurti and Herve This began their collaboration and proposed molecular and physical gastronomy. After Kurti's death in 1998, the term was changed to molecular gastronomy.

1992 Nicholas Kurti and Herve This initiate the International Molecular Gastronomy Conference

In 1995, Herve This founded the Institute of Gastronomic Sciences at the Collège de France in Paris.

2001 British chef Heston Blumenthal launches the show Chemistry in the Kitchen on the Discovery Channel

2003 Ferran Adria, Heston Blumenthal, Emile Jung and Herve This start the Inicon project, an international molecular gastronomy research project

In 2003, the first large-scale international molecular gastronomy conference was held in Madrid, Spain

In 2003, Ferran Adria put his meloncaviar (melon imitation caviar) on the menu for the first time, and the Sferification technology began to mature.

In 2006, four great molecular gastronomy masters issued a joint statement defining molecular gastronomy.

In 2007, Norwegian physicist Martin Lersch began studying food flavor pairing.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Slow-cooked silver cod)

3. What is Molecular Gastronomy?

This is arguably the most food-conscious place in the world. Over two thousand years ago, when food and clothing were still a struggle, the saying "never tire of fine food, never tire of delicate delicacies" gained widespread recognition, and its influence remains even greater today. It's no wonder, then, that the Western-inspired "molecular gastronomy" is so popular.

The concept of "molecular gastronomy" was only coined in 1988, but within the past 20 years, numerous restaurants with the same name have sprung up around the world. With scientifically charged terms like "molecule," "analysis," "element," and "mechanism," coupled with descriptions like "experience," "creativity," "art," "style," "specialty," and "imagination," molecular gastronomy undoubtedly represents the "high-end" and "fashionable" aspects of gastronomy.

Molecular gastronomy, which transforms food and creates avant-garde culinary experiences, has recently spread from Spain and Europe to Asia. This magical creation, reminiscent of the Spanish surrealist painter Dalí, has a 125-year wait list at its original Spanish restaurant, El Bulli, and a price tag of NT$8,000. Now available in Taiwan, it's now available at at least five restaurants, with prices starting in the hundreds of NT$. Albert Adri arrived in Beijing with two documentaries about el Bulli and his new book, "Natura." Perhaps the biggest surprise came from those media editors who, with their own imaginative portrayal of molecular gastronomy as a chemistry experiment. This has led to two biased perceptions over a long period of time: first, it is believed that molecular cooking kitchens are like chemical laboratories, filled with syringes, measuring cups, alcohol stoves and other experimental equipment, making it seem as if chefs also have to wear gloves and masks; second, it is believed that only foods that seem to be "putting the cart before the horse" can be called molecular cuisine, such as soup that is solid, fish roe that is full of juice, or food served with smoke or covered in foam with various flavors.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Low-Temperature Fruit Collection)

The opinions of various countries;

1. America

In June 2008, Food Technology, the journal of the Institute of Food Technologists, published a lengthy introduction to molecular gastronomy, describing it as a fusion of science and culinary art. However, the founder of molecular gastronomy was deeply dissatisfied with this description, publishing an article in the same journal in December of that year stating that this statement was fundamentally wrong. So, what exactly is molecular gastronomy? And how does it relate to trendy "molecular cuisine"?

In America's best-equipped restaurant kitchens, the hot new gadget isn't a high-powered oven or a reliable freezer; it's the kind of precision-controlled heating apparatus used by chemists in their experiments—the kind that's submerged in water.

Today, some of the West's most sought-after chefs use these heaters to cook their favorite dishes at precisely the right low temperatures. Some chefs are studying the absorption properties of starch in different foods. Others are even experimenting with chemicals that aim to coagulate proteins in their natural state, where they normally wouldn't.

Moto: How bizarre is Chicago? Liquid nitrogen, centrifuges, high-pressure guns, and other experimental machines are everywhere. How awesome is it? A cutting-edge restaurant, well-deserved of its reputation. Signature dish: a one-dish menu. You heard right, and the menu tastes exactly as it says on the menu. It's said to be the most avant-garde and novel restaurant on the planet. Here, you'll be constantly captivated by the sheer variety of food and sights! Here, you can see food floating before your eyes, eat food printed out by Canon printers, and even eat food prepared with industrial lasers. You might even catch the chef using a medical syringe to fill colorful balloons with chocolate sauce. Liquid nitrogen, centrifuges, high-pressure guns, and other machines are everywhere, and all sorts of bizarre foods are constantly appearing before your eyes. The show is about to begin, and who even remembers eating? The waiter will bring you the appetizer—a one-dish menu. You heard right, and the menu tastes exactly as it says on the menu. For example, the Italian main course menu tastes like a blend of mozzarella, basil, and tomato, while the French menu is reminiscent of soft cheese on a baguette. A dish called "Maki" rolls looks very similar to Japanese sushi, filled with rice, crab meat, etc.

There are many famous molecular gastronomy restaurants in the United States, such as Alinea.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Low-temperature pan-fried scallops and vegetables)

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Low-temperature pan-fried scallops and vegetables)2. France

Kitchen lore is as shrouded in mystery as it is in the fog. Cookbooks, both Chinese and Western, are filled with countless "tricks" and "secrets." For example: adding a little lemon juice to pear jam keeps it white, while a cobalt pot with a tin lid will turn it red; mayonnaise won't work for menstruating women; mayonnaise won't work on a full moon; the oil and eggs need to be at the same temperature to make mayonnaise; removing the head of a suckling pig immediately after taking it out of the oven makes the skin crispier; and there's a crucial distinction between the proper position of the meat over the fire when roasting. Every cookbook is filled with these secrets, yet we don't know why they exist or whether they're true or false. Nicholas Kurti, a physics professor at Oxford University and a keen cook, once said, "I think it's a tragedy that we can measure the temperature of Venus' atmosphere but don't know what's going on in soufflé." Another French culinary enthusiast, Hervé This, is also fascinated by these culinary tricks. He began collecting these legends, which he calls "culinary precisions," in the early 1980s and has since collected over 25,000. He is more interested in using scientific methods to investigate the authenticity of these "precisions" and the underlying scientific principles.

In 1988, Curti and Teece jointly proposed a new discipline: "molecular and physical gastronomy." Teece later simplified it to "molecular gastronomy," which is what we now call "molecular gastronomy."

Molecular gastronomy does not create delicious food

Many people know about "nanotechnology" from the overwhelming advertisements for "nano refrigerators" and "nano washing machines." However, the "nano" in these advertisements has nothing to do with actual nanotechnology; it's simply a scientific term used to deceive the public. And for many, "molecular gastronomy" simply refers to the overpriced, exotic food served in "molecular gastronomy restaurants."

However, Tiss repeatedly emphasized that molecular gastronomy is neither culinary nor art; it is science, and only science. He even argued that chefs can learn scientific knowledge and understand art, but science itself cannot be combined with art. In his view, art creates emotion, while science creates knowledge. Science is science! Molecular gastronomy, like physics and chemistry, is a pure science. It is part of "food science," but unlike other areas of food science, it focuses primarily on industrially produced foods, while molecular gastronomy is primarily focused on the kitchens of homes and restaurants.

What is commonly referred to as "molecular gastronomy" is actually the product of "molecular cooking." For the average person, such classification and definitional issues aren't particularly important, and confusing the two is harmless. In fact, this conceptual confusion is not unrelated to Tiss himself. In his doctoral dissertation, he outlined five goals for "molecular gastronomy": 1. Collect and study culinary legends; 2. Develop mechanistic models of existing recipes to elucidate changes in the cooking process; 3. Introduce new tools, materials, and methods into cooking; 4. Apply the knowledge gained from the first three goals to develop new dishes; and 5. Increase public interest in science. He defined molecular gastronomy as a pure science, but the third and fourth goals were merely technological applications, while the fifth fell into the realm of education. He later expressed surprise that no one on his doctoral dissertation committee, which included two Nobel laureates, raised any objections. He subsequently dropped the last three goals, retaining only the first two. However, he realized that the ultimate goal of cooking is ultimately to please the customer—and that "artistry" and "love" are essential elements in achieving this ultimate goal. 6. Therefore, in addition to using science to explain the physical and chemical changes in cooking, we must also explore the factors of "art" and "love" involved.

These conceptual definitions are obviously a bit confusing, but we can ignore them. What we care about is what these things mean to us, not what they are called.

Now that we know that it's the vitamin C in lemon juice that keeps a peeled pear's color, there's no need to use actual lemons; dissolving a vitamin C tablet in water might be more economical and convenient. To create a mushroom aroma, you don't need mushrooms themselves, but rather the flavoring substances within them. And adding ionone to corn soup—will it make violet lovers scream?

Molecular gastronomy teaches us that ice cream is created by stirring the ingredients at low temperatures, creating a large number of bubbles. Adding liquid nitrogen can also produce the same effect. Therefore, using liquid nitrogen to make ice cream, or to quick-freeze other food ingredients, is a common practice in molecular gastronomy restaurants. Its appeal lies primarily in its unexpectedness.

Take mayonnaise, for example. The traditional recipe consists of egg yolks, oil, vinegar, and salt. In molecular gastronomy, it's an emulsion, but with a high oil content and a low water content, it's a semisolid rather than a liquid. Physically, it's oil dispersed in water, forming tiny droplets. The yolk acts as an emulsion. With oil and an effective emulsifier, you can make "mayonnaise." Egg whites, for example, are also excellent emulsifiers. By gradually adding oil while beating the egg whites, you can create "yolk-free mayonnaise." Another variation is to dissolve gelatin in hot water, blend at high speed, and then add oil. The result is "eggless mayonnaise." The gelatin here acts as an emulsifier and also creates a gelatinous structure that traps the oil droplets. If the "water" used is a solution or broth of something else, like chicken broth or vanilla extract, then the customer sees "mayonnaise," but tastes like "chicken" or "vanilla." For those accustomed to the taste of egg yolk, wouldn't that be quite shocking?

Even if you don't like the taste of oil, you can use melted chocolate instead of oil - the soft texture, the rich chocolate aroma, what would you call it? This is the "mayonnaise" of molecular cooking.

The combination of "molecules" and "cooking" seems very discordant. It is called "Molecular Gastronomy" in English, which subverts people's traditional concept of food.

Developed in the 1980s by French scientist Hervé This and Oxford University physics professor Nicholas Kurti, the concept applies principles from chemistry, physics, and other sciences to the cooking process, preparation, and ingredients. Chefs identify the ideal cooking methods and temperatures to create dishes with unique sensory qualities, based on the molecular connections between ingredients.

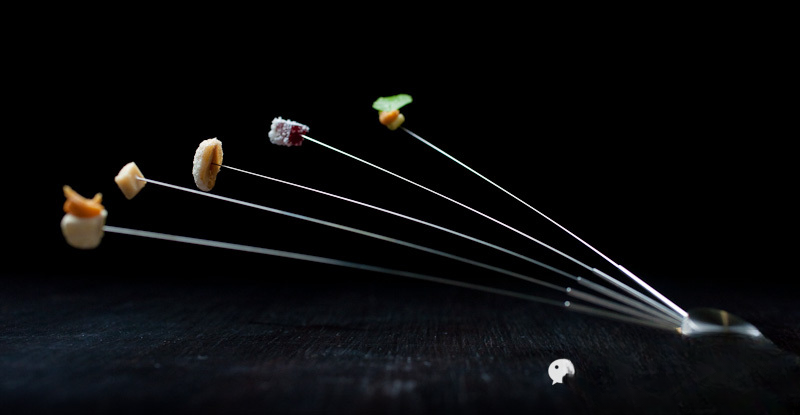

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Molecular Flavor Snack Combination)

4. London, England

In December 2006, the London weekly The Observer published a joint statement by four molecular gastronomy pioneers and masters. In an effort to clarify public and media misunderstandings of their culinary research, Ferran Andria, Heston Blumenthal, Thomas Keller, and Harold McGee summarized molecular gastronomy in the following four points:

1. The principles of molecular gastronomy are: openness, authenticity, and excellence

2. The basis of molecular cuisine is to protect traditional cooking and make progress on this basis.

3. The core of molecular cuisine is innovation, including innovation in raw materials, cooking techniques, kitchen utensils and information expansion.

4. The belief of molecular cuisine is: humanity. Only when people communicate with each other can the potential of molecular cuisine be truly realized.

This first point addresses the view that molecular gastronomy is like industrial food, loaded with chemical additives, focused solely on effects without regard for human health. All ingredients used in molecular gastronomy have been researched and verified by chemists, medical scientists, and biologists to be harmless to the human body. The second point addresses the view of some traditional chefs and gourmets that molecular gastronomy represents a betrayal of tradition. Molecular gastronomy pursues perfection. It first affirms traditional cooking methods, then defines optimal taste and texture, and finds solutions to problems that traditional cooking cannot address. The third point defines the scope of molecular gastronomy's innovation, a very broad scope encompassing innovation in all aspects of gastronomy. The fourth point calls for the sincere collaboration of molecular gastronomy experts worldwide, breaking the traditional closed-door research and secret recipe practices to promote the development of molecular gastronomy as a whole.

Speaking of the current trend of molecular cooking, I'm sure my fellow culinary professionals have heard of it. Lately, I've been getting calls from many friends and former acquaintances asking me what molecules are all about. It seems the emergence of molecular cooking has sparked curiosity and also gained some recognition from all walks of life. While I've been researching molecules lately, I've discovered many misconceptions about them, especially those who pretend to understand them. However, true understanding of molecules in China is very limited. Some people often think they understand molecular knowledge simply by making molecular foams and pearls. Molecules are vast and profound, worthy of continued research. So-called pearls and foams are merely the surface of molecular knowledge. Another major misconception is that many catering companies now buy a lot of molecular equipment and follow recipes from others. Is there any point? How many actually understand the underlying physical principles and chemical structures? Why do they do this? Simply ignoring culinary truths for the sake of trendiness, distorting the concept of molecular cooking, and changing the physical form of objects doesn't necessarily make them right. We need a deeper study of the physical properties and chemical principles to achieve more rational, not haphazard, cooking.

The kitchen is like a science lab, and cooking is another form of scientific experiment. Imagine a chemistry lab. You'll find chemicals, of course, but also containers for mixing and reacting them, devices for controlling the temperature of the reactions, and equipment for measuring the amounts of chemicals for each reaction. And perhaps less familiar, instruments for determining the products of the reactions—instruments that tell you the results of the experiment.

Your kitchen also has all sorts of gadgets—instruments for heating and cooling, for mixing, cutting and grinding, for weighing ingredients—and all sorts of raw materials (i.e., food ingredients) with which you can perform chemical reactions.

Every time you cook a dish from a recipe, you're conducting an experiment. You measure the ingredients according to the recipe's instructions, mix (or react) them, and then taste the dish to test the results. Then, using the scientific method, you test your results by comparing the taste and texture of your dish to the photo in the cookbook. Often, you're disappointed—the photo in the cookbook is always better than your first attempt. So you try again, changing things up a bit.

Good chefs use their experience to adjust temperatures and the ratios of ingredients in food to improve it. A scientifically minded chef will examine the instructions in a recipe and ask why they are made as they are and whether they could be modified. Applying science to home and restaurant cooking has developed into a new discipline called molecular gastronomy—the application of scientific principles to the understanding and improvement of food.

Over the past decade, molecular gastronomy has largely taken shape through meetings held by a group of chefs, scientists, and food writers at the Ettore Majorana Scientific and Cultural Center in Erice, Sicily. These meetings (International Symposiums on Molecular and Physical Gastronomy) were initiated by Elizabeth Thomas, then director of a California culinary school, and shaped by the late Nicolas Coti, a leading low-temperature physicist of the 20th century. Since Nicolas Coti's passing, I have assisted Dr. Hervé This of the Ecole de Paris in establishing Studio Erice.

The broad range of topics explored in these workshops helped shape the emerging discipline of molecular gastronomy. While those of us who work in molecular gastronomy have primarily been working to address interdisciplinary questions, all of these efforts have been aimed at developing a specialized discipline for cooking food, encompassing the entire process from ingredient preparation to the finished dish.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: The Endless Life of Molecular Gastronomy)

(Guo Hongxiao's work: The Endless Life of Molecular Gastronomy)5. Spain

Molecular gastronomy involves cooking dishes based on the molecular connections between ingredients—think chocolate and caviar, asparagus and licorice, or eggs and bacon ice cream. Blumen and Adrià both dislike the term "molecular gastronomy," preferring to be seen as culinary adventurers. Adrià told The Times: "I'm thrilled and delighted with what Bulldog and Spanish cooking have achieved. It's a testament to the fact that Spanish cooking is now the most celebrated culinary art in the world, and a testament to the culture of innovation among incredibly innovative chefs who continually surprise and delight their customers."

In today's culinary world, molecular gastronomy has always been a topic of discussion and exchange among chefs from all over the world. It is also a new thing that chefs who like avant-garde cooking methods talk about with relish. It is also at the forefront of topics discussed in the catering industry.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Dry-cured ham slices)

6. Europe

Currently, the most popular equipment in restaurants and hotels in Europe and the United States has evolved from automated cooking equipment and utensils to more technologically advanced, precision-controlled heaters. Chefs in Europe and the United States are using these submersible heaters to cook dishes at a more precise, low temperature. This method improves the absorption properties of starch in various foods, allowing proteins to coagulate without coagulating, making nutrients more easily converted and absorbed by the body. This cooking method and theory, known as "molecular gastronomy," has become increasingly popular among Western chefs. The fundamental principle of this culinary discipline is to incorporate molecular science into the cooking process, cooking based on the molecular connections between ingredients. This allows for better food compatibility and meets the needs of the human body. Molecular gastronomy can also unlock the mysteries of culinary creation, such as identifying the optimal cooking temperature for proteins and imparting distinct structures to foods. Chefs around the world are actively practicing molecular gastronomy. Advanced science and technology are helping us understand the true meaning of cooking. Whether we are professional chefs or home cooks, this will not only transform the way we prepare food, but also potentially revolutionize the way we all live and work.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: High-temperature paper crab and yellow tofu pudding)

The term "molecular gastronomy" (Gastronomie moléculaire in French) seems to categorize it as fringe science. Generally speaking, as new disciplines arising from the intersection and interpenetration of basic and related disciplines, fringe science rarely creates large-scale material value immediately; rather, it requires a period of in-depth research and development.

This is "molecular gastronomy," a trend that's becoming increasingly popular among Western chefs. The term essentially refers to infusing cooking with a deeper understanding of the molecular connections between ingredients—think chocolate and caviar, asparagus and licorice. This promises to improve food compatibility and satisfy the human body's needs. Sometimes molecular gastronomy demystifies certain aspects of gourmet cooking; other times, it can be used to find the optimal temperature for cooking proteins or impart different textures to foods.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Stir-fried Snails with Sichuan Peppercorns)

Today, the chemical reactions and physical processes in the kitchen are becoming a serious area of research at universities, with papers and monographs published one after another. Why are bay leaves so fragrant? Why do cherries have a slightly bitter almond flavor? Centuries of kitchen experience and wisdom passed down can be used in the laboratory to identify authenticity and uncover the secrets behind them.

In the traditional sense, innovation in dishes means seeking to arrange and combine different ingredients with different cooking methods. To innovate in cooking, it is not enough to start from the taste alone, but it is necessary to attack the sense of touch and vision.

This can only be achieved with the help of modern scientific instruments and equipment. Perhaps this is the magic of today's molecular gastronomy.

Molecular gastronomy is a cooking method based on the molecular connections between different ingredients. It attempts to gradually transform laboratory equipment into culinary tools, allowing for better food pairing and satisfying the human body. As an emerging culinary method, its development requires the collaborative efforts of restaurant chefs, physicists, and chemists.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Spring in the Garden)

In its purest sense, molecular gastronomy is the science of applying the principles of chemistry and physics to cooking. Today, the term has become synonymous with innovative cooking styles and chefs who are avant-garde and know how to combine cutting-edge science, technology, and even psychology.

Molecular gastronomy – a science

Although chefs have been applying techniques learned from others or developed on their own to cooking for centuries, and scientists have been bringing scientific theories to explain the world we live in for centuries, it was only in recent decades that scientists began to study the physical and chemical reactions involved in cooking food, just as they do in other areas of research.

Molecular gastronomy – a style

This experimental style in culinary art not only coincided with, but also followed the development of the science of molecular gastronomy, quickly becoming known by the same name. Because many of these experiments, including new understandings of culinary science and the use of materials and techniques, represent the latest generation of high-tech developments, the name is apt. However, many chefs and foodies would not consider this style "modern," "forward-thinking," "experimental," or even "deconstructive." The debate over what to call this style is raging, and I intend to let scientists, chefs, and foodies debate it.

Molecular food is a molecular-level substance that can be expressed by molecular formulas and is made by using engineering technology to process natural, synthetic, and biological raw materials that are edible to humans. It is formulated differently according to the lifespan and health needs of the human body.

Such foods can have flavors unrelated to the ingredients. For example, "bacon and eggs" made from vegetarian food taste exactly like real bacon and eggs, even though they don't contain any meat. The secret lies in scientists analyzing and extracting the molecules in real bacon and eggs that produce taste sensations, producing them as "molecular foods," and then adding them to vegetarian dishes.

(Guo Hongxiao's work: Fake Lemon Balls)

"Waiter, serve!" Immediately, you're greeted by syringes, test tubes, measuring cups, and the like. This scene is undoubtedly startling. Is it too strong? Have you mistakenly entered a laboratory or some other place? It's bound to leave you perplexed. This kind of experience is called "molecular gastronomy." In many European countries, due to its high price, it was initially only accessible to the upper class. It's also a favorite restaurant of many celebrities, a symbol of both status and fashion. What is molecular gastronomy? Simply put, it's the application of chemistry to cooking, reorganizing the molecular structure of food. This maximizes the nutrients in the food and ensures the body's optimal intake. Molecular gastronomy is fascinating because what you see is always different from what you experience. A fine wine might dissolve into gas upon entering your mouth. It might taste like chicken, but it doesn't. You might look like caviar, but it's actually lychee...

(JACK) Introduction of Master Guo Hongxiao:

Guo Hongxiao, known as the "Culinary Picasso" of molecular gastronomy, is the forerunner of molecular gastronomy, the godfather of molecular gastronomy, and the recipient of the Gold Medal for the Asian Dissemination of Molecular Gastronomy. Born in 1989, he is one of the earliest chefs in China to explore molecular gastronomy and the Honorary President of the Molecular Gastronomy Association. He is an International Master of Culinary Arts, recipient of the French Le Cordon Bleu, the Star of Excellence Award from the French Gastronomy Association, the Knight of the Order of the Asia-Pacific International Chef, the Gold Medal of the International Master of Culinary Arts, a national judge in the catering industry, and a member of the Chinese and Western Cuisine Committee. He has won over ten gold medals in various international competitions. He is the Chief Technical Director of the Zhengzhou New Thinking Molecular Gastronomy Culinary Center.

In 2007, Mr. Guo Hongxiao collaborated with Michelin-starred chefs in the United States, Spain, and Germany, systematically studying the various techniques of molecular gastronomy. He also received guidance and support from Ivy Tiss, a member of the French Academy of Physics and the father of molecular gastronomy. He learned the molecular culinary techniques of the world's avant-garde art school. Under the guidance and influence of international and domestic chefs, he brought the essence of Spanish molecular cuisine to the world and is promoting the integration of molecular culinary techniques with new dishes.

In 2009, he founded the New Thinking Zhengzhou Molecular Gastronomy Official Culinary Center in Zhengzhou, where he regularly teaches and explains the elements of popular Western molecular cuisine, including creative cooking courses. His work has garnered widespread attention from high-end hotel and restaurant chefs. His technical analysis of molecular cooking techniques, published in the magazine "Oriental Cuisine Culinary Artist," has caused a stir within the industry. He has presented hundreds of lectures and demonstrations on the fundamentals of molecular cooking, including molecular gastronomy-inspired dishes, for renowned chefs in cities such as Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Xi'an, Beijing, Zhengzhou, Wuxi, Nanjing, Luoyang, Wenzhou, and Ningbo.

In 2010, he was invited by the International Federation of Chefs to train molecular cooking techniques for famous chefs from well-developed restaurants in Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Shanghai. He was awarded the titles of Molecular Gastronomy Cooking Expert, Molecular Gastronomy Communication Ambassador, and the Catering Industry Cultural Contribution Award. Mr. Guo Hongxiao has devoted himself to studying the internationally popular molecular cooking techniques. He has purchased European Michelin molecular cooking books and equipment from the United States, Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom and other places, spending hundreds of thousands of dollars to study the latest international trend molecular technology. He has trained hundreds of high-end hotel molecular gastronomy chefs. Hundreds of hotels have benefited. He has broken the monopoly of foreign catering equipment on professional tools for molecular cooking equipment, and independently developed a number of domestically produced molecular cooking equipment and some creative molecular tools. The quality and effect have reached international standards. He has also been cooperating with chefs from the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom to study the application of new science and technology and equipment.

In 2012, he published "Molecular Gastronomy," mainland China's first simplified Chinese book on molecular cooking. It's divided into theoretical and culinary chapters, and features a foreword by Avril Tissé, the French physicist and chemist who founded and founded molecular gastronomy. The book has been recommended to renowned chefs in Europe and abroad. Guo Hongxiao has quietly injected fresh blood into the restaurant industry, becoming a true propagator of molecular cooking, deeply rooted in the industry.

In 2013, he was awarded the title of Godfather of Molecular Gastronomy.

In 2014, he was invited to perform molecular gastronomy on Shenzhen TV's "Men Left Women Right" program. In 2014, he won the Asian Molecular Gastronomy Communication Gold Award.