250 precious old photos tell the story of this botanical garden that changed the world

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, is a must-see attraction on a visit to the UK for plant lovers and nature enthusiasts, but Kew is more than just a tourist attraction.

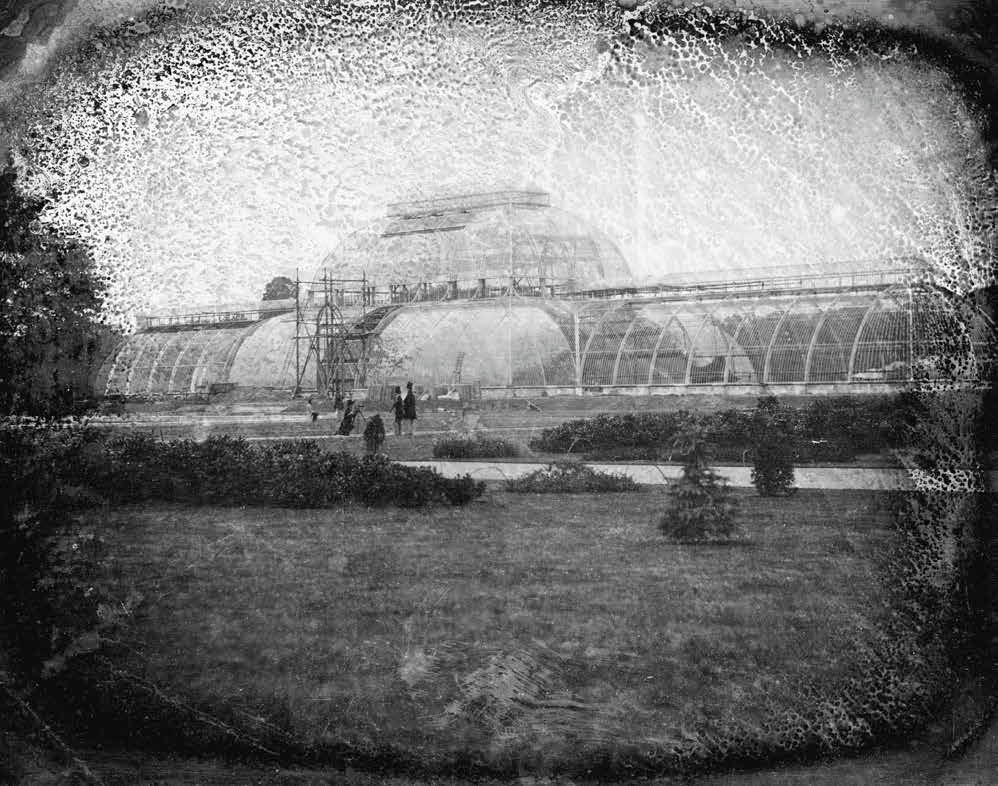

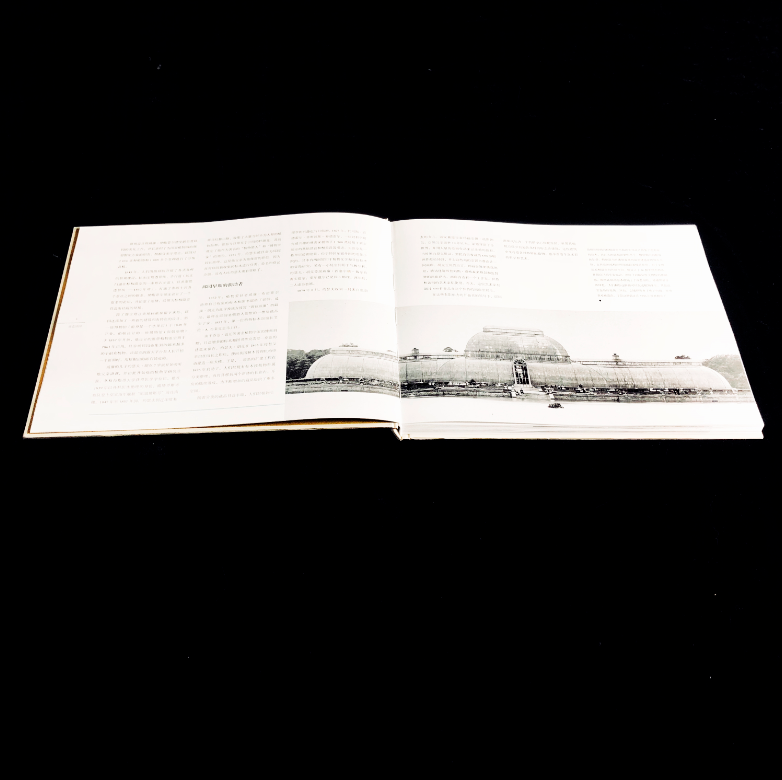

This earliest photograph of the exterior of the Palm House was taken using the daguerreotype process. This technique was developed in 1839 and remained popular until the 1850s. The image was displayed on a copper plate that was coated with a thin layer of silver and highly polished. Because of the camera, the image was very small. The daguerreotype was very fragile and sensitive to touch, and its mirror-like surface required tilting at an angle to be viewed. It did not withstand wear and tear, and the colors faded easily.

In 1840, Kew Gardens was transformed from a declining royal botanic garden into a public institution and gradually entered its heyday, and photography technology also emerged at this time . A large number of historically significant photos about colonial expansion, trade, industry, medicine, war, and even the values of Victorian Britain have been preserved.

Thousands of precious photographs are also preserved in Kew's archives and art collections. These photos come from a wide range of sources, from commercial postcards to expedition albums, from professional photographers' portfolios to personal photography. Kew staff carefully selected them and compiled them into a book called "The Story of Kew" .

This book covers the construction process of Kew Gardens' landscape architecture, how Kew Gardens collects plants and receives visitors, the coordination and cooperation of staff in various departments of Kew Gardens, and historical memories such as the trauma Kew Gardens suffered during the war years and its post-war reconstruction.

The development of modern photography technology has preserved and linked these historical details. We seem to have walked into the development of Kew Gardens over a century, seeing and hearing the people and events in those beautiful moments...

1.

Kew Gardens was originally a large strip of farmland belonging to a private estate. Since the 16th century, the royal family living next to Richmond has brought prosperity to the area.

Sir William Chambers designed a number of classical-style temples around Kew Gardens; architecturally, the Temple of the Sun, built in 1761, reflects a revival of interest in classicism.

On the night of March 28, 1916, a violent storm brought down a cedar of Lebanon on the roofs of the decorative buildings at Kew Gardens. The storm also killed the last of the Seven Sisters of Elms, which were said to have been planted by the daughters of George III.

After the development and decline during the reigns of George II, George IV and William IV, Kew Gardens was transformed from a private royal botanic garden into a national forest management office in 1840. Industry leader William Hooker turned the tide at this time and brought Kew Gardens back to life.

In 1844, construction of the Palm House began. Under his and his successors' far-sighted leadership, Kew Gardens has maintained its international leadership despite the changes.

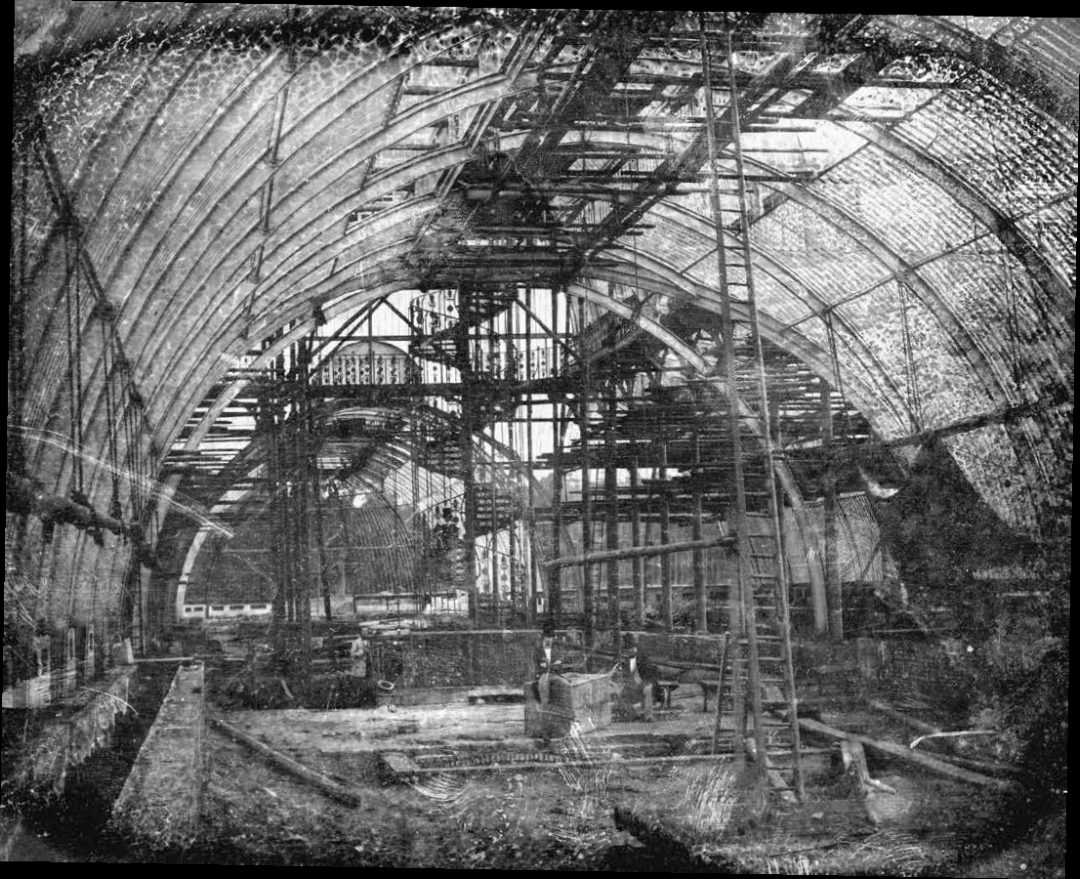

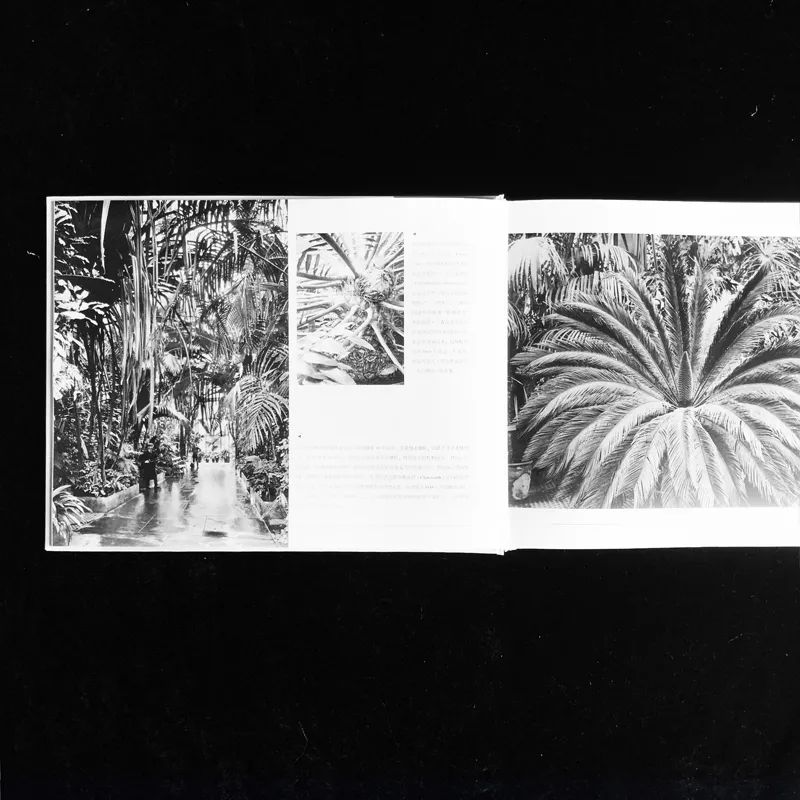

This is the first photograph of the interior of the Palm House, taken on July 24, 1847, while the house was still under construction.

In 1843, Queen Victoria donated 18 hectares of Royal Gardens, which were dedicated to the cultivation of trees. In 1848, William Nussfield took on the arduous task of creating the National Arboretum. The cultivation work took three years, and William Hooker declared that this was "perhaps the most complete collection of plant species ever collected in a single arboretum."

2.

Before the advent of photography, naturalists would use sketches to quickly outline the plants they collected and studied, the landscapes they visited, and the different cultures they came into contact with.

Joseph Hooker, son of William Hooker, began traveling in the mid-19th century, when photography was in its infancy. Photographic equipment was large, complicated, cumbersome, and easily damaged, so he chose to paint a lot to record the culture and landscape he encountered. But photography inevitably became an important technology, and on his journey to the United States, Hooker bought photos of the big trees he observed.

By the early 20th century, photographic equipment had become much more portable, allowing plant hunters like Ernest Wilson to record every aspect of their journeys, including their camps, the local people, and the plants they found.

Wilson photographed the cones of this species, native to southeastern China and Taiwan, on a street in Badong County, Hubei Province, in 1910. The cones are framed by a mural and the image of a man in the background, showing exquisite detail. This photo was commissioned by Wilson to take during his second visit to the Arnold Arboretum. He carried negatives with him, and could only see the final image when he returned home and developed the negatives into prints.

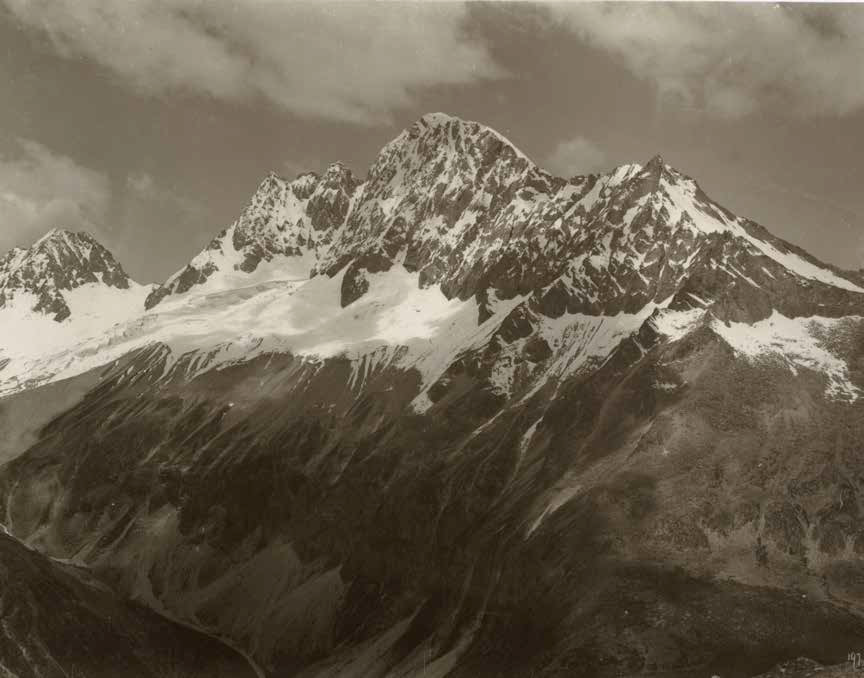

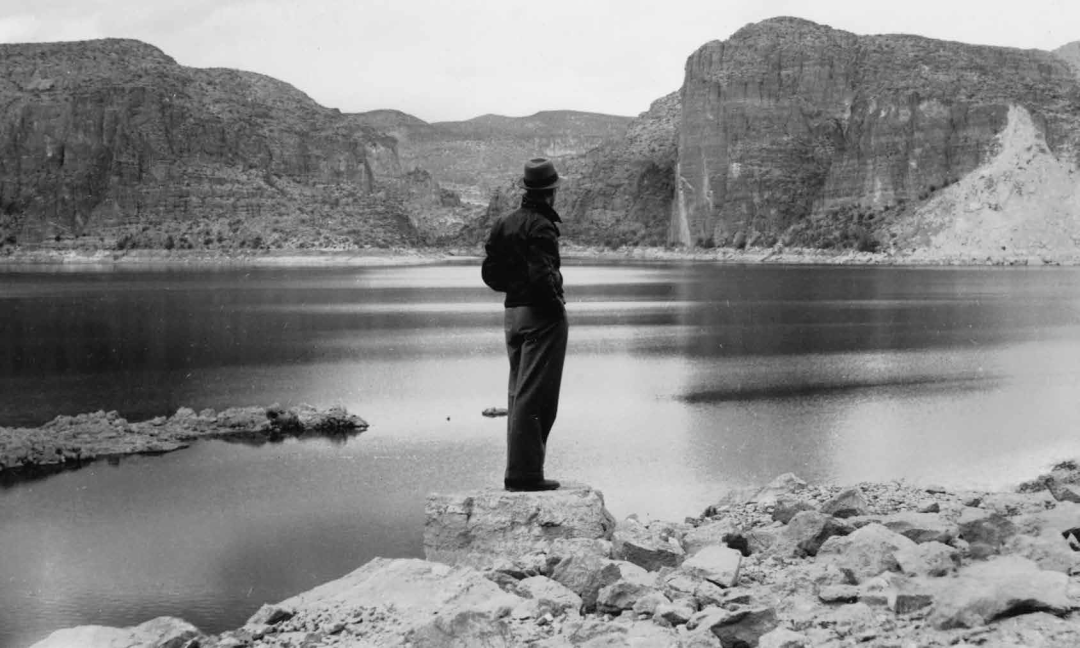

These photos show the difficult environments that plant hunters and botanists had to work in, such as high mountains, desert wastelands, and dense jungles, which they still had to travel through without modern equipment and maps. As shown here, Ross-Innes is crossing a mountain and we see him collecting specimens. Sometimes, plant hunters were the first Westerners to visit these places, and they were obviously impressed by the local scenery and plant specimens. The photo on the left shows Ross-Innes admiring the scenery he encountered.

3.

Kew Gardens is all about the people and their work both on and off the stage. Photography is the only way to capture these precious moments.

In the 19th century, the concept of public gardens and leisure gardens suddenly became popular, and many parks were gradually built into places for people to spend their leisure time. Kew Gardens could not withstand the pressure and also increased its opening hours and provided public facilities.

The oldest entrance to Kew Gardens is the main entrance to Kew Gardens Green, which was built in 1825 when Kew Gardens was still owned by the royal family. This gate was set up to prevent "vulgar and curious civilians" from entering the royal territory. Originally, there were two houses on both sides of the gate, with a stone statue of a lion and a unicorn standing on each house.

When William Hooker was director, he thought the public gardens deserved a more impressive entrance, and the main gate at the entrance was designed by Decimus Burton and first opened in 1846. The pillars are carved from Portland stone; the reliefs of fruit and flowers on the columns and the Royal House coat of arms on the gate are in keeping with Kew's identity as a new botanical research institution.

Kew Palace is the oldest building in Kew Gardens. It was built in 1631 by a businessman named Samuel Fortrey. About 100 years later, it was rented by Queen Caroline and then bought by George III. It was the royal country house until it was opened to the public in 1898. The palace played an important role in the development of Kew Gardens. It was because of the royal family's residence that the botanical gardens had the opportunity to be born, and it also laid the foundation for the current Kew Gardens. Today, the public can still visit the palace.

In the early 1870s, although Joseph Hooker made concessions in his struggle with the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, he still successfully defended Kew Gardens' position as a scientific institution and ensured its future development.

In 1912, the rock garden was rebuilt. Due to a lack of sufficient stones, logs and stumps were disguised as stone. Materials from demolished buildings were hidden from view. As the bog garden was expanded, the dripping well in the photo was removed and a waterfall was added.

Kew Gardens is a large institution with hundreds of staff. Most of the staff work behind the scenes, playing different roles from gardeners, scientists, museum curators to artists and administrators. Kew Gardens would not be what it is today without the hard work of generations of Kew Gardeners.

This small shed is part of the Tropical Plant Department's nursery, next to one of the greenhouses, which supplies thousands of plants to the main exhibition greenhouse. Boxes under the workbench contain a mixture of loam, peat and gravel for potting seedlings. Leaf humus and sheep manure collected from Kew and nearby parks are also added to the mix.

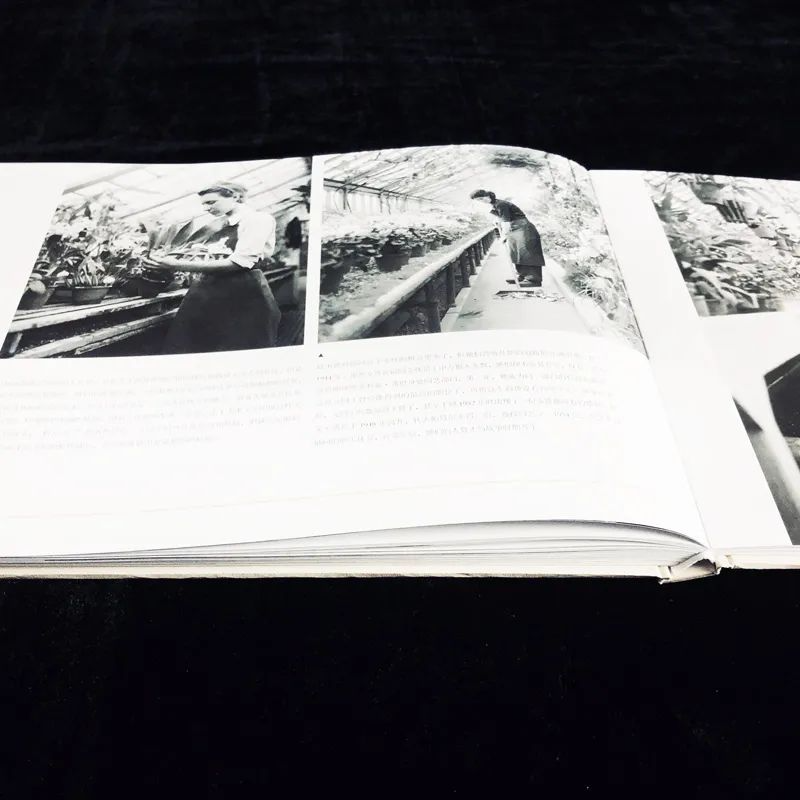

In 1896, Kew Gardens recruited its first batch of female gardeners. In order not to distract their male colleagues and prevent romance between employees, they had to wear a not-so-attractive uniform of brown bloomers, woolen stockings, waistcoats, jackets and peaked caps.

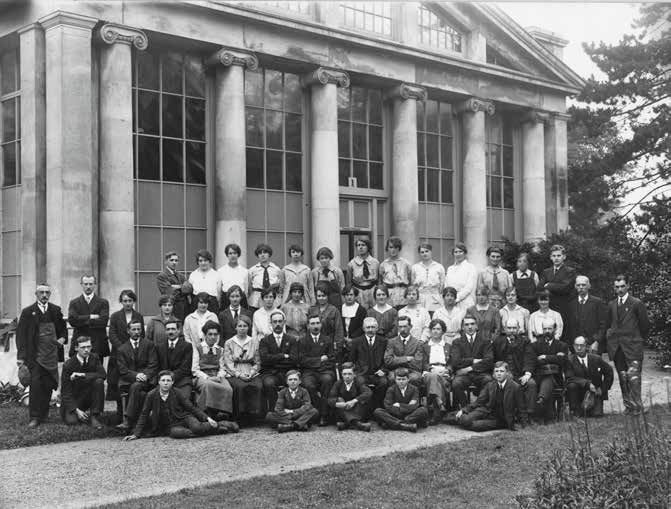

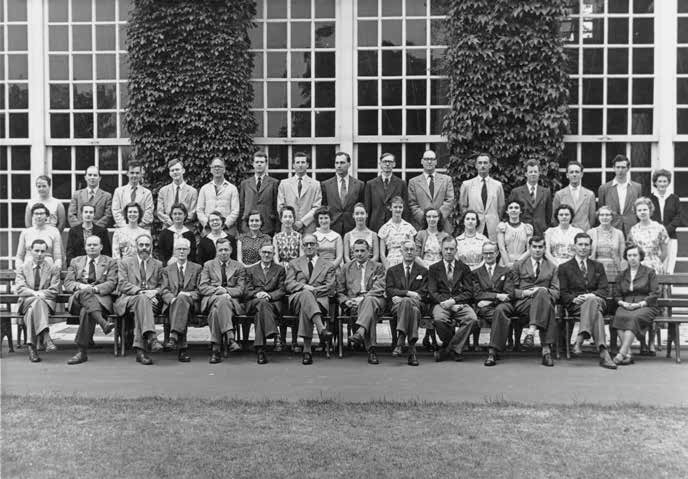

Every year, Kew staff gather for a group photo. The following selection of photos, taken about 20 years apart, gives a glimpse into the changes in fashion and demographics of the staff at Kew. For example, the photo taken during World War I (1916) shows many female staff, while photos taken after that show almost no women. In addition, this photo shows that Kew employed male children at the time, who started working at an early age.

Two employees are working in the mounting room. After drying and flattening the collected specimens, they will staple the specimens to a piece of archival paper and affix an identification label on the lower right corner of the paper. The label states the source of the specimen, the collector, the family name and genus number, the botanical name, and other information, such as the use of the plant at the collection site.

The mounted specimens are stored in the specimen cabinet in the order of family, origin, genus and species. The auxiliary specimens, mainly fruits and seeds, are of equally important taxonomic value. However, research materials such as fruits are often too large to be fixed on the paper, so they have to be separated into auxiliary specimens and main specimens, which complement each other. In addition, the flowers of the orchid family are fragile, so people will collect the fragments to make auxiliary specimens, otherwise it will be difficult to ensure their formal integrity.

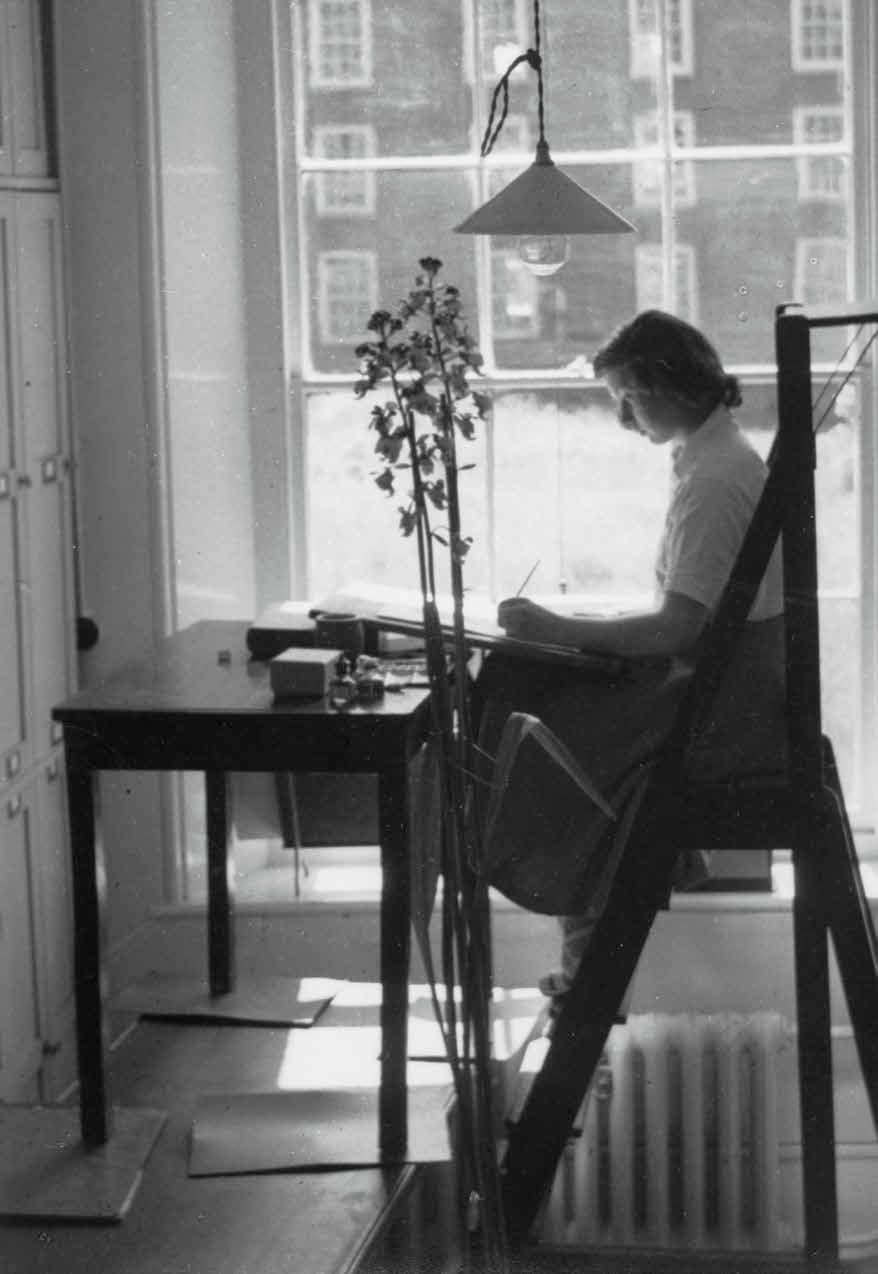

Ann Webster studied at Guildford School of Art and became a freelance botanical illustrator, contributing to Curtis Botanical Magazine, Flora of Tropical East Africa and Kew publications. Here she is depicting the Rose-shaped Orchid, a tall orchid with purple-red flowers. The photo, taken in 1951, illustrates the difficulties botanical artists often face in approaching their subjects.

As the Jadrell Laboratory expanded, so did the number of employees. In 1960, Charles Metcalf had three employees, and a new building was built as the Cell and Physiology Departments were established. By 1964, the laboratory had 20 permanent employees. This photo was taken in 1963 outside the old Jadrell Laboratory. Metcalf is standing in the center of the photo.

In the 1940s, Dr. Hutchinson was the director of the museum and Dr. Robert Melville was one of his scientists. Here, Melville is seen scraping pollen from a gerbera onto a glass slide. The pollen grains are collected as part of the National Reference Collections Program, which helps identify pollens that cause pollen allergies. Melville was one of Kew's representatives to the British government's Vegetable Medicines Supply Committee, providing advice on medicinal plant resources.

Life at Kew Gardens continued uninterrupted during the two world wars.

In order to make the British people self-sufficient, public land was divided into small allotments. Kew Gardens took on a new function - creating a "demonstration" allotment field to try to guide the public in the best way to grow their own vegetables, and also reclaimed some land for local residents to use. Women made an indelible contribution to the development of Kew Gardens at this time.

John Wilfred Thatch was born on 8 November 1923 and worked as a gardener at the T-glass, Palm House and Arboretum. At the age of 18, he left Kew to join the army and joined the 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry as a tank driver. In the summer of 1944, he served in Normandy and was eventually killed in the Siege of Falaise.

In December 1915, the Kew Society Journal reported: "For the last nine months the First World War has overshadowed everything." At the annual meeting that year, the Society's president proposed a toast to the Royal Army and commented that "the Kew folks are doing their best". With the exception of one married worker, all staff of military age (under 40) and eligible for service had enlisted. Women took on many tasks; in 1915 alone, 24 of the 38 permanent gardeners were women.

The female gardeners who arrived at Kew Gardens were quickly integrated into the workforce and received generous support from their male colleagues who were previously unaccustomed to working with women.

After World War II, Kew began to develop more partnerships with botanical gardens and scientific institutions around the world. Overseas horticulturists could come to Kew for training, rather than going to colonial botanical gardens established with the help of former Kew members. JA Obi of the Nigerian Ministry of Agriculture works in a greenhouse at Kew Gardens, pruning the inflorescence of an anthurium plant to stimulate leaf growth.

Within 100 years of its completion, the Palm House gradually fell into disrepair. The warm, humid environment of the house had an adverse effect on the structure, and the ironwork corroded and then expanded and contracted. As a result, large sections of window panes broke off and fell to the ground, and makeshift solutions were sometimes resorted to, as shown here. A major renovation was carried out in 1929, but it was not enough; in 1951, an engineer's report recommended that the Palm House should be demolished and rebuilt, in keeping with the post-World War II ethos of getting rid of the old and welcoming the new.

4.

A series of static photos take us back to the past, perhaps just the design of a flower or a blade of grass, a brick or a tile, or just a leisurely afternoon tea moment or a moment when plant hunters sit on the ground. These seemingly ordinary and simple scenes tell of the passion and hard work that generations of Kew Gardens staff have devoted their entire lives to.

The girl in this photograph, taken in 1923, is thought to be "Miss Cotton", most likely the daughter of Arthur Cotton, then keeper of the Herbarium and Library at Kew Gardens. The girl appears uneasy as she sits in an awkward position on the giant leaf of the Victoria amazonica, which is said to support up to 45kg if the load is evenly distributed.

Daffodils hold a special place in British culture. They are praised in paintings and poems, and symbolize the arrival of spring. They are perhaps the most popular garden plant. In the 19th century, the first weekend of April was celebrated as "Daffodil Sunday" in Kew Gardens and throughout London. At that time, people would pick flowers from their own gardens and give them to patients in local hospitals. Today, from February to May every year, the wooden boardwalks of Kew Gardens are surrounded by a yellow carpet of more than 100,000 daffodils.

The quiet Rhododendron Valley, Queen Charlotte's country house, ancient Greek-Roman stone carvings, the much-loved daffodils, the first rose trellis and other arrangements have injected vitality and vigor into Kew Gardens...

In "The Story of Kew Gardens", whether it is these precious photos obtained through thousands of dangers, Julia Margaret Cameron's portrait photography, Ernest Wilson's plant notes, or the palm greenhouse photographed using the silver plate photography method, the T-shaped greenhouse in the era of stereoscopic photography, etc., these precious photos carry the development path of modern photography technology and also awaken the affectionate past of a botanical garden of love.

The Story of Kew

Click the picture to add to favorites